- Home

- McWatters, Nikki;

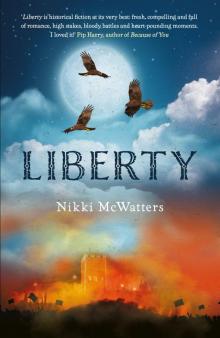

Liberty

Liberty Read online

Nikki McWatters was shortlisted in the 2010 Queensland Premier’s Literary Award Emerging Writer category. She has published two memoirs: One Way or Another (2012) and Madness, Mayhem and Motherhood (2018); and two young adult novels: Sandy Feet (2014) and Hexenhaus (2016). She won the Irish Moth Award (2016) and has written for the Sydney Morning Herald, Huffington Post UK and The Big Issue. She is currently the spokesperson for the annual Vinnies CEO Sleepout. Nikki also has a law degree in her bottom drawer somewhere.

nikkimcwatters.wordpress.com

Also by Nikki McWatters:

Saga (2019)

Liberty (2018)

Hexenhaus (2016)

Sandy Feet (2014)

For Mia

I walked alone, against my father’s strict instructions, at high sun on the morning of the summer solstice, away from the city of Beauvais toward the neighbouring forest of oaks and chestnuts. This forest was my place in the world, my own personal grove of solace. It was a beautiful singing place and I came to it often, to feel the contours of the earth beneath my boots and the sound of my voice, hollow and smooth, merging with nature. I walked through the carpet of leaves and acorn husks, reaching out to touch the trees with my fingers.

I had memories of this wood that seemed to go back beyond time. It was as if the forest was within me as much I was within it. I sang as I walked. Old songs that my father told me my mother had sung to me as a babe. It was a warm day and I soaked myself in the scents of wild pear and beech. I pulled my cap from my head and shook my dark hair loose and wandered on through the woods, swinging my basket by my side, already imagining the taste of berries bursting against my tongue. In a small circular clearing, I stopped and lifted my face to the warmth of the sun, breathed deeply and watched three swallows circling above.

It was in this place that I could feel my mother. The breeze was her breath; my footsteps on the dirt, her heartbeat. As I ducked beneath a low-hanging branch and felt the tickle of a spider’s web on my face, I imagined it was her kiss against my cheek. Something of her spirit still dwelled in the forest, clinging to the moss and leaves like an invisible spectre. She made this place feel safe and comforting to me, but my father would never set foot in the forest again, fearing it was a haunted and sad place. Yes, I felt her strongly. She had been only a little older than me when she’d taken her last steps in this very spot.

I needed this solitude because life within the city walls of Beauvais was stifling and it was easy to feel crushed by its bustle and noise. The people living there were wedged into small rooms, all boxed in on one another like chickens in a coop. In the quarter where I lived with my father, we had two small rooms and an attic above; the smells and sounds of our neighbours filled our ears from morning to night. Cabbages and quarrels. On the narrow streets and marketplace, voices were constantly raised to the point that my ears rang. There were fights. Robberies. Beggars. And the smells hung like an oily fog in the back of my throat.

The small forest grove was my secret place. Every small noise was crisp and beautiful. The crackling of sticks and leaves beneath some wood-creature’s paws. A bird. The wind. The scents were intoxicating. I imagined I could even smell the warmth of the sunlight that fell through the tree leaves like golden sleet. It smelled like freshly baked bread. My skin, my eyes and ears all seemed to open a little more, like morning petals, to take it all in.

And I felt close to something so much bigger than myself, like I was a part of an enormous secret. I was tempted many times to bring Colin to my special place but always talked myself out of doing so. I loved Colin as much as I loved my father, but even so, deep down I wanted to keep this place for myself. Just me. It was all I had that was my own. Apart from the memories of my mother. It was ‘our’ place.

‘Between the ox and the donkey, sleeps, sleeps, sleeps the little son, la-la-la,’ I sang to the trees.

I held a good tune, or so my father had always told me, yet I sang much better with an audience of insects and birds than of people. And as the words to the old song bounced from branch to branch I let all my fears and sadness wash away. In those sacred moments there was just the music and no mourning for my mother, whose face had long been washed from my memory; no clammy terror that the fighting up north would eventually move down closer toward Paris to tread over us as the fishwives gossiped over laundry lines; no creeping discomfort about the way the Lieutenant watched me with a wolfish leer, touching me whenever I passed him in the street.

‘Between roses and lilies, sleeps, sleeps, sleeps the little son, la-la-la.’

I searched the undergrowth for anything I could carry home: wild herbs, mushrooms, berries. The birds were my musicians, chirping in tune like feathered lute-players. A butterfly zigzagged past, disappearing into the shadows.

And then the birds stopped singing.

I stood stone-still, ears pricked.

Everything – the entire forest, the sky above, the earth below – seemed to become as if a tableau in a painting. Still and silent. It was unnerving. I waited. Not sure if I should move or run or remain frozen. Or just keep singing.

Something invaded the silence. I listened earnestly. It was the sound of a horse, walking slowly and steadily. The clump of its shoes against the dirt echoed out from the dim shadows of the forest. It was like the beat of a funeral drum.

All of my father’s warnings about the forest came rushing at me like wild flood water. My stomach balled into a knot, my pulse quickened. The skin on my arms prickled, puckering into goose flesh. I steeled myself, trying to summon courage. Silently I begged my mother to lend me some of her own brave heart.

‘Halt and announce yourself,’ I called.

Still the hooves approached. Clop. Clop. Clop. My muscles tensed, ready and defensive. Groups of marauding men and desperate soldiers were known to roam the forest roads and deeper into the woods, looking for stragglers to rob – or worse. I turned with a graceful spin and my hand reached down for one of the small hatchets hidden in my basket. I stood, took aim and threw it, watching breathlessly as it cart-wheeled, whistling through the air. The small axe landed with a heavy thud, the sharp blade wedged into the trunk of a pine tree. I had the other out of the basket and in my hand, ready to follow the warning shot with a more malevolent one. My father had forged the metal and fashioned the small hatchets for me, and had taught me to use them with great precision.

‘A girl needs to protect herself,’ he’d told me on my thirteenth birthday.

‘From what?’ I had laughed so innocently.

And then he had sat me down and told me the truth of my mother’s death and for the first time in my life all those years of town whispers made sense. I learned that there was plenty to be afraid of in the world. I learned that I was lucky to be alive and that my father wanted me to be able to defend myself because my mother had not been able to.

I had not had cause to use my small hatchets, although I often practised with them in the forest. I had the aim of a king’s marksman and a good strong arm.

‘I said halt,’ I called again in a loud voice, trying to sound much braver than I felt. ‘I am armed and you have been warned.’

I saw the horse stagger into the clearing. Slung like a limp sack over its long stooped neck, fallen forward, was a bloodied man. I gasped. At first, I thought he was dead but he reached up an arm and lifted his head.

‘Help me.’

His hair was dirty, wild and caked with blood. His unshaven face was grey. Without letting my eyes leave his face, I pulled my hatchet from the gnarled tree trunk and held the two of them defensively out in front of me as I edged warily around the horse, closer to the path so I could run if this was trickery.

�

�Where have you come from?’ I asked, making sure he could see I was armed.

‘Roye,’ he gasped. ‘The Bold has sacked it. We surrendered but still he butchered us. Soldiers. Men. Women. Even children.’

I looked at him. His torn jacket had brass buttons. His boots were of good quality. He appeared to be unarmed.

‘Are they coming for Beauvais next?’ I asked, dreading his answer.

‘I can’t say,’ he said, grimacing in pain. As he lifted his arm again toward me I saw a gaping hole in his chest. ‘But I think … so … yes …’

‘You are hurt badly,’ I whispered. ‘Can you move forward? I will ride you to town so you can warn the Captain of Beauvais. He needs to prepare for the worst.’

I could not steer a horse and carry my basket at the same time so I left it where it lay. I would return for it later. I tied the two hatchets securely at my sides beneath my outer skirts so that they did not show and then pulled myself up behind the saddle and pushed the man forward as gently as I could. He groaned. The horse did not look well either so I did not press her hard. In a gentle trot we made our way to Beauvais. The soldier closed his eyes and I prayed that he would not die before we arrived.

The horse clattered along the dusty road. We came to a break in the trees and saw Beauvais, the wonder of the whole region. There was the Cathedral, massive and magnificent, cresting the hilltop in the morning sun. The steeples and towers dwarfed the stone walls that surrounded the city. The many houses of Beauvais were cobbled together, all at chaotic angles.

As we drew closer, the gatehouse on the far side of the bridge came into view. Two round towers stood on either side of the pointed arch and in a shallow niche, a statue of King Louis XI looked down. Beauvais was a proud town. I only hoped that she would prove strong enough to resist an invasion.

We crossed over the bridge and I smelled the muddy banks of the brook beneath. I held my breath and tried to ignore the piles of refuse that had slid down into thick quagmires of human waste, rotting meat and animal carcasses. Two men, chests bared, were further downstream, among the green grasses and reeds, hauling a barrel of excrement from the back of a cart to empty it into the water. For all of Beauvais’ grand beauty as a city, her outskirts displayed all the disgusting features of a bloated glutton.

I urged the horse to go faster, hastening on to the city gates, which were open. A group of urchins with dirty faces appeared.

‘What you got there?’

‘Is he dead?’

‘Did you kill him?’

‘Can I have his boots?’

Their clothes were filthy and their faces even filthier. I ignored them and pushed on under the shadow of the gatehouse into the busy streets, making my way into the town with my sorry cargo and a heavy sense of foreboding. Charles the Bold was the villain leading the Burgundian army and was determined to take as much of France for himself as he could. With all our men away fighting with King Louis, Beauvais would be an easy town to take. I felt sick in the belly as I guided the horse past curious bystanders. I had never been one for talk of battles and politics but it had been impossible to ignore the ill-wind that had begun to blow through my beloved city over the past few months.

The roads in the merchant quarter were uneven and sodden after a week of rain. Other ponies and packhorses clopped through the town and russet-coloured peasants shouted in coarse voices.

‘Hot sheep’s feet, ribs of beef, many a pie!’ a street vendor hollered.

Once I turned the ailing nag into the wider, sunnier streets where people wore high colours and soft fabrics, the looks my way became more repulsed than curious. I passed through the wide and handsome prospect of Church Street where some of the finest houses and inns sat, and stopped outside the Captain’s mansion. I reached forward to rest a hand on the soldier to check that he was still breathing as he appeared to have fallen asleep, or worse.

A black-robed Dominican friar with a kind, round face was just leaving the Captain’s house. He helped me down from the horse.

‘I will call the Captain’s men to take him inside,’ he said and showed me to the door, ringing the bell loudly. ‘You did the right thing to bring him straight here. The Burgundians, you say? He looks half-dead or more. It seems I will be sending his soul heavenward with prayer shortly.’

Not knowing what else to do, I followed the Captain’s men inside as they carried the limp, broken soldier. It was bold and foolhardy but my concern for my city and my curiosity about the interior of the house got the better of me. I felt small and meek in the palatial manor house. I had only ever delivered bread to the kitchen-maids at the servant’s entrance. The main parlour room was like a dream. Soft furnishings and thick, deep floor rugs with the glint of gold, and fine glossy china adorning the smooth polished cedar side-tables.

‘What the devil are you doing here, you soot-urchin?’ the Captain yelled as he blustered in from the kitchens, his hair wild and his face bloated with surprise and anger.

‘I found an injured soldier in the woods just beyond the city gates,’ I said in a small voice, looking down at my boots. ‘Before he fell to silence, he told me that the Burgundians have sacked Roye and that they may be marching for Beauvais. I rode him directly here on his own horse, which will also need some attention.’

‘We have a garrison here of only three hundred men!’ Captain Louis de Balagny shouted into my face as if this was somehow my fault. He looked to the ceiling. ‘We must pack up and leave town or surrender peacefully.’

He seemed panicked. A far cry from the stern and sombre captain I usually saw speaking to the townsfolk in the square. The injured soldier had been taken to an upstairs room and a doctor had been summoned. I prayed that the soldier would survive.

‘Sir, the soldier told me,’ I ventured nervously, ‘that the town of Roye had offered a peaceful surrender but Charles the Bold had slaughtered and sacked them anyway.’

Balagny turned and glared at me.

‘Perhaps you heard him wrong, girl.’ He frowned. ‘Are you not Jeanne, the daughter of Matthew the Coward? Not really very reliable stock.’ He narrowed his eyes at me. ‘What were you doing in the forest alone anyway?’

‘I just … I …’ I stammered. ‘I like to walk and … pick berries.’

‘A girl wandering unchaperoned in the forest? You ask for trouble. Had that fellow upstairs felt more … um … lively, well, things might have gone badly for you. I would not tempt fate, girl. You look like your mother, uncannily so. You wouldn’t want to end the way she did.’

I felt sick. I knew what he meant and wondered if I was right to pray for the survival of the unknown soldier. He might have been a horrible person.

‘I did not venture too far,’ I mumbled. ‘And I can run fast and look after myself.’

‘Big talk for a peasant girl with holes in her shoes,’ he laughed roughly. ‘And how would you look after yourself, child? Kick your little feet with your toes poking out? Bundle your small, delicate fists into clubs to take down a gang of thugs?’

I drifted into nervous silence, thinking of the small hatchets beneath my skirts. It was a crime for a woman to carry a weapon. A sudden panic gripped me. If the soldier awoke to tell them that he had been rescued by a girl wielding axes, I would have a lot of explaining to do. Although I’d been named for the brave and saintly Jeanne d’Arc who had been a distant kinswoman of my mother and a heroine of childhood stories told to me by my father, I doubted I could muster her courage and iron will if accused of bearing arms.

‘Lagoy?’ the Captain turned his attention to his lieutenant, Jean Lagoy, who had just entered the room. I looked down at my boots again to avoid his gaze, bile rising in my gullet at the sound of his name.

‘He’s in a sorry state,’ the deep voice rumbled. ‘But he’ll live, I’d wager.’

‘This girl is telling a story about the fellow having come from Roye claimi

ng that the Burgundians are headed for Beauvais.’

‘I said he wasn’t sure,’ I muttered. ‘He only thought they were … but … he … well … he couldn’t be certain.’

‘I think we should wait for the soldier from Roye to wake and speak to us,’ Lagoy said thoughtfully. ‘Perhaps Charles the Bold will bypass us on his way to Paris. I could take some men and ride toward Paris, recruiting reinforcements, perhaps?’

Jean Lagoy then crossed the room to me and took my hand. ‘Thank you, Mademoiselle Laisné, for bringing him to us. That was very brave of you.’

I looked up at him and my cheeks burned. His hand was clammy with sweat and his fingers massaged mine. His touch was blatantly sensuous and unpleasant. The brash and dashing young Lieutenant had pursued me for nearly a year but I had no interest in him. I found his arrogance unbearable. Whenever I was anywhere near him, he made me feel like a trapped animal. His eyes bore into mine.

‘Go now, girl,’ Captain Balagny barked. ‘Back to your cowardly father. And see that you say nothing of this business or you will cause a panic we can ill afford. If anyone asks, tell them the man you escorted into town was a vagabond, a drunkard. And cover your head for pity’s sake, girl. Have you no shame? Remember your station. Did a stint in the pillories teach you nothing?’

I fumbled in my pocket for my cap, then securing it on my head, I scurried from the room, giving an awkward curtsey and nod, cursing myself that I had forgotten to tie it back on when leaving the forest. As I stepped outside I felt a hand grip mine and I turned sharply to see that Lagoy had followed me into the street.

‘Jeanne, ma chérie,’ he said, glaring down at me with his dark, thickly lashed eyes.

‘I must get home to my father,’ I frowned.

‘When will you come dancing with me?’ he grinned.

‘I am not of your station, Sir,’ I replied. ‘I could no sooner go dancing with you than the King.’

‘Perhaps some private dancing in the stables out the back. We could go riding. I have a new horse. I think you would like him. He’s quite a stallion.’

Liberty

Liberty